I can’t quite work out photographer Roe Ethridge’s work, which I like. He takes some unexpected shots, he’s not always technically precise (he makes no bones about showing pixellated, blurred or re-photographed prints in his gallery shows) but there’s something fascinating, weird and ‘off’ about his vision which really appeals. With his recent Rockaways project and his editorial shoots for titles like Art Review, the now sadly defunct Tar, and Proenza Schouler’s edition of A Magazine, he’s one of the coolest young photographers working today, who has a somewhat skewed individual vision.

His images can be nostalgic, often irreverent and disconcerting, and whilst they're often downbeat they’re never morbid or sinister; he captures a real feeling and mood with his work. The portraits are particularly odd - the sitters often looking away, or blinking or seeming confused in the frames Ethridge chooses to show. And yet they work as strong images because of this very weirdness. The influence of Paul Outerbridge Jr is unmistakeable, and I see parallels with the painter John Currin too (who he has, incidently, photographed), but Ethridge himself is now influencing a whole raft of younger photographers, particularly in New York. As disconnected as many of the images shown here are, when you see a group of them together they do form an offbeat narrative, and you get a real sense of Roe’s World. As Ethridge himself says “One of the reasons I've been so interested in this kind of displaced, broad scope approach is an effort to embrace the arbitrariness of the image and image making. For me serendipity and intention are both necessary.”

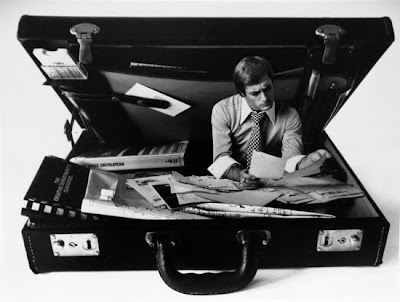

For his latest project for Vice magazine he’s teamed up with perfomance artist Miranda July to shoot a series based around incidental characters who appear only fleetingly on screen in some cultish films from the last 30 or 40 years. How they decided on these minor characters I'm not sure, but there's a sense of calculated obscurity to the project. The series seems like a smart progression from the deliberately uncomfortable studio fashion work Ethridge had been producing, and although July comes dangerously close to Cindy Sherman territory in this work, Ethridge’s photography, with its sombre lighting and uneasy composition, moves the images away from this and makes for a fresh take on editorial fashion.

Below is the new series working with Miranda July and stills from the films they’ve referenced, followed by an overview of Ethridge’s work from the past few years.

+2008.jpg)